History

From Civil War to the 1970s

Research into the pre-Civil war history of the 360 acres on which the present Fort Lincoln community was built can lead to head scratching results. One line of research could result in the conclusion that identifying the acreage as “Fort Lincoln” is misleading. And that is because there is also some basis for concluding that the actual “Fort Lincoln” was built in Maryland, starting on August 26, 1861, at a location (Old Baltimore Pike) some 2-1/2 miles from the District of Columbia.

Here is an example of that confusing history. One historical source, discussing the ring of forts built during the Civil War, states: “Each fort was also uniquely designed to make the best use of local topography. The ridge extending through present-day Fort Lincoln, known as Prospect Hill at the time, made it an ideal site for one of the new fortifications. It offered clear views that enabled Union troops to monitor potential raiding targets in the area, including Bladensburg Road and the B&O Railroad line to the west and the Anacostia River to the east.”

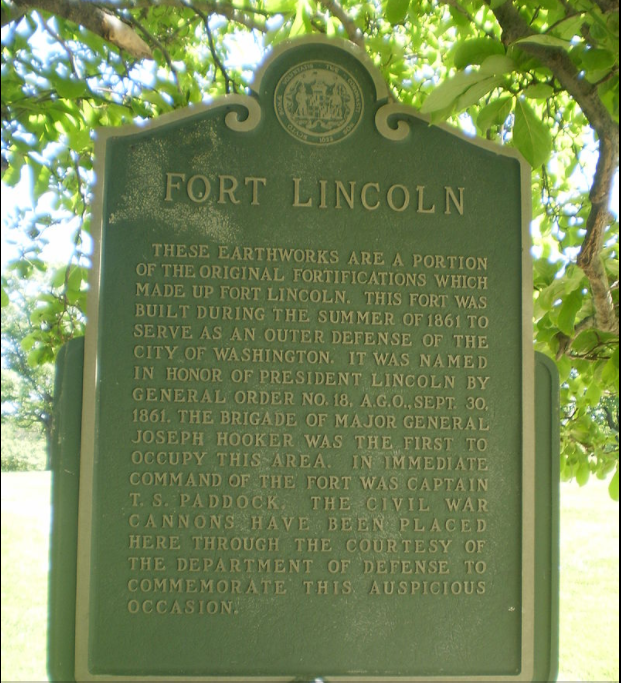

Prospect Hill, however, appears to have been in Bladensburg, Maryland, which is reached by driving some miles northeast from the D.C. line, on Bladensburg Road. In any event, whether within today’s District of Columbia boundaries or not, Fort Lincoln was named in honor of President Abraham Lincoln by General Order No. 18, A.G.O., on Sept. 30, 1861. Although there were more than a few scares throughout the Civil War, the capital was never seriously threatened. Today, the majority of the remaining fort is within Fort Lincoln Cemetery, across the D.C. line, in Prince George’s County, Maryland and can be visited. A marker has been placed in the cemetery to commemorate the fort.

A less conflicting history of Fort Lincoln following the Civil War, and preceding the 1970s, can be found in Robert Malesky’s October 9, 2017 article, A Home for America’s Bad Boys.

That published history of Fort Lincoln, as we know it today, begins in 1866 when Congress passed a bill to establish a “House of Correction for the District of Columbia” in the Georgetown section of D.C., and took control of it. The first few boys were assigned there in 1870. Within two years, deeming the soggy western location unhealthy and the buildings uninhabitable, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to purchase a new site. He chose a 150-acre tract in northeast D.C., with the option to buy 100 adjacent acres. It was on high ground with clear views and fresh breezes.

The United States Reform School Farm, established in 1871, moved in 1872 from Georgetown to what grew to be well over 250 acres off Bladensburg Road near South Dakota Avenue.

The vacant federal land was known as Fort Lincoln for the Civil War fort thought to be partially located on the site. When the House of Corrections moved to the Fort Lincoln site, they quickly began construction. First came a barn that would temporarily house the boys, then they contracted with Edward Clark, Architect of the Capitol, to build a grand main building that would sit at the apex of the hill. In 1876, the name was changed from the House of Correction to The Reform School of the District of Columbia, making it sound a little less penal. Throughout the next decades the school grew steadily as the nation’s system of juvenile justice evolved. The dormitories were called cottages and each held sixty or so boys.

By the end of the century, the average daily population of the school was 219. Two-thirds of those were from the District, but the others had been sent from federal courts around the country. DC’s Reform School had always been a hybrid, housing both District delinquents, and non-District boys convicted of breaking federal laws. Early in the country’s history, federal crimes such as counterfeiting, treason, or postal violations were almost exclusively committed by adults. By the dawn of the 20th century, new crimes were changing that. Driving a stolen car across state lines was a federal offense, as was making moonshine; both pursuits in which boys readily engaged.

In 1905 the main campus was destroyed by fire, decimating administrative offices, the Superintendent’s quarters, and several other buildings. Evidence of the fire was uncovered during a 2007-2008 archeological study, including the recovery of architectural debris fragments and pieces of ceramics, glass bottles, and toys – all reflecting school life at the turn of the century.

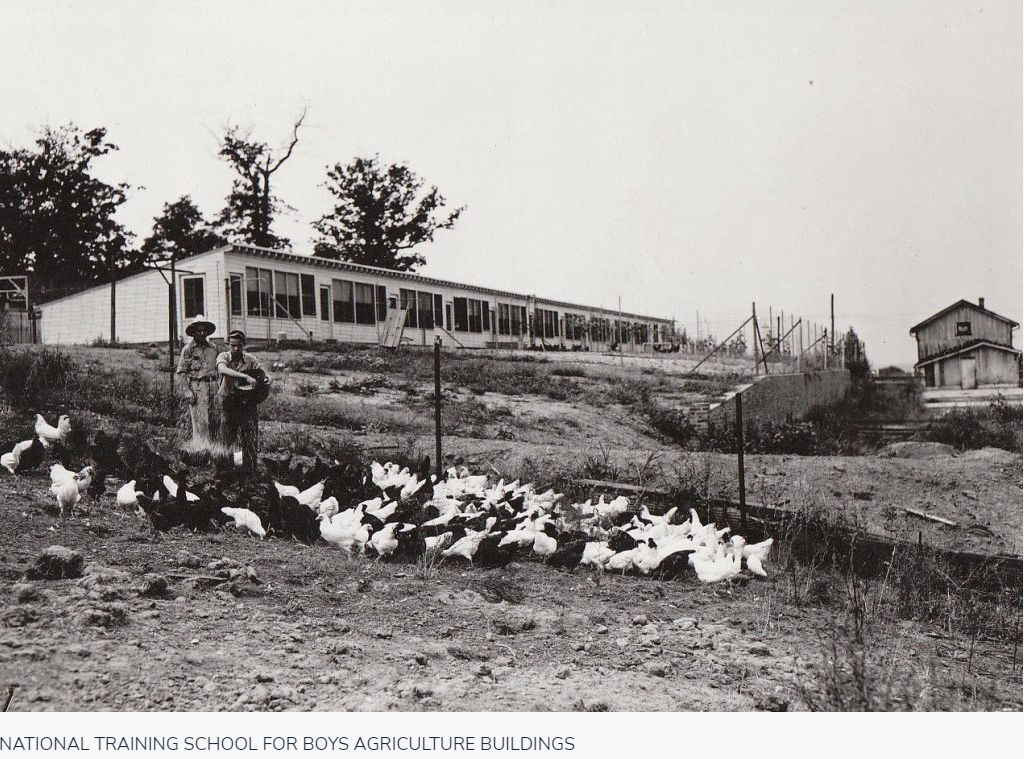

In 1908, Congress changed the name for a final time to the National Training School for Boys, which better signified its growing role housing federal delinquents. The new name reflected a shift in mission as well. Previous associations with punishment and incarceration were eschewed for a more modern approach emphasizing reform, education and the stimulation of learning, vocation, and citizenship.

In a June 12, 1912 article published in The Washington Post, “p. L22,” the school was described as being “located on one of the most picturesquely beautiful sites in the country, moral and physical health and mental growth must necessarily be stimulated by such surrounding.” According to the article, the boys were always busy either with study or learning a trade. The buildings were described as splendid, extremely sanitary, and very modern.

It was not an easy life for the boys. Daily work routines were often exhausting, and discipline could be harsh. The NTSB housed both African American and white youths, but they were segregated. Corporal punishment was the norm, though counseling and group therapy became more prevalent by the mid-20th century. There were also reports of sexual abuse, though it did not seem as widespread at the well-regulated NTSB as in many state institutions across the country.

The school remained in operation throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Among its more famous young residents were Charles Manson and Frank Morris, one of the only three men believed to have escaped Alcatraz Prison. In the early 1960s it was decided that a newer, more modern facility was needed, and plans were made to build a new campus in Morgantown, West Virginia. In May of 1968, the school’s doors were closed for the last time. There were many different ideas for what to do with the Fort Lincoln property. One man who had his eye on it was President Lyndon Johnson. He thought it would make an ideal site for an experiment he had in mind to illustrate what he meant by “The Great Society.”

View of the National Training School for Boys, standing at South Dakota Avenue & Bladensburg Road and looking northeast in February 1968.

Dormitories of the National Training School for Boys. The view, from South Dakota Avenue looking northward, was taken in February of 1968.

1970s - Present

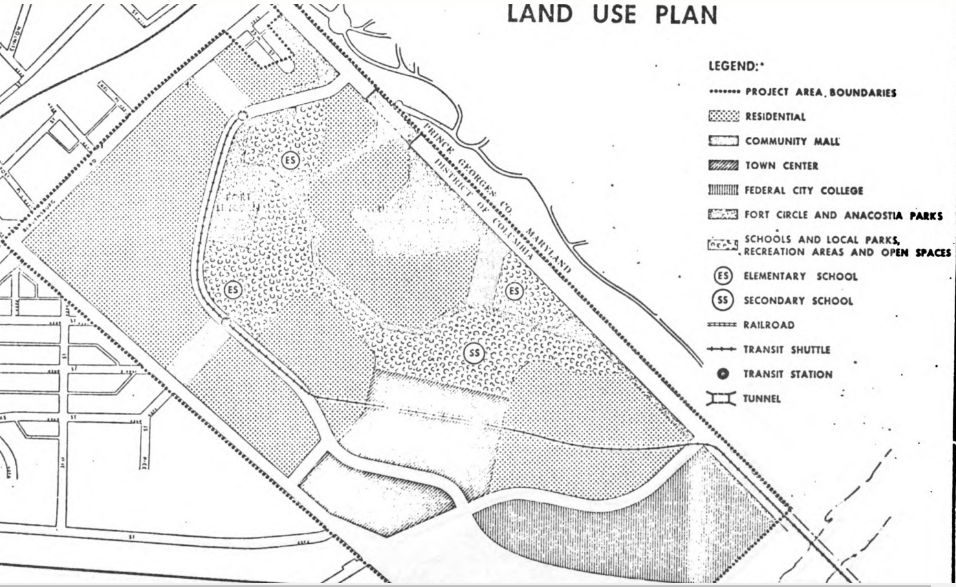

In 1967, just before the National Training School moved to West Virginia, President Lyndon Johnson, as part of his Great Society program, began looking for surplus federal land around the country to provide a staging ground for innovative residential/commercial developments. He envisioned Ft. Lincoln’s soon to be available acreage as an opportunity for a partnership between government, the private sector and the community. A Fort Lincoln Urban Renewal Plan was adopted by the National Capital Planning Commission, and ratified by the D.C. Council in 1972, as a blueprint for this three-party partnership.

When the Fort Lincoln Land Disposition Agreement was drafted, one housing development already existed on the land that adjoined the Fort Lincoln Urban Renewal Area.

That single family housing development, with homes built as far back as the 1920’s, is shown in the upper left hand portion of the drawing. It is a one block long insert and comprises the 3100 block of 35th Street, N.E. And to its right, as you face the drawing, is a pebbled area that the accompanying 1975 legend describes as “. . . local park][], recreation area[] and open space[].”

Thus, a wide swath of the land immediately north and east of the already developed 3100 block of 35th Street, N.E. was specifically reserved for park, recreation and open space. And so, for that reason, the National Park Service retained title to 1.1 acres of the 3.1 acres that surrounds the 3100 block of 35th Street, N.E

The objectives President Johnson had in mind when he directed the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development to partner with the D.C. government, was to develop the 360 acres of surplus federal land in northeast D.C. as a “planned community.” It was supposed to be a “new town in town” to test the ideas of his Great Society and thereby “show the world that the United States could overcome urban blight and integrate well-planned communities racially and economically.”

To that end, Fort Lincoln was supposed to incorporate “a top quality design” that would attract “affluent whites [who] would share schools and parks with lower income people of color . . .”, because, at the time, race was an absolute predictor of income.

To implement the visionary Fort Lincoln Urban Renewal Plan, the D.C. Redevelopment Land Agency commissioned a lengthy study, which was completed in 1972, with substantial input from community organizations in northeast D.C., the city fathers and the federal government. Acting on behalf of the city and federal government, the RLA then sought, over a two and a half year period, to negotiate terms for a development contract that would provide District of Columbia residents generally, and future Fort Lincoln residents in particular, with an opportunity to participate in and benefit from the employment, planning, construction and profit-making opportunities the huge development offered.

The initial out of state developer balked at putting up $300,000 of its own cash as part of the development deal. It instead

proposed to make a local minority developer a partner and have that developer put up the funds. The RLA rejected that tact and the out of state developer then withdrew from the effort.

The local developer, a self-made millionaire named Theodore Hagans, immediately launched an effort to persuade the RLA to allow a company he had formed [Fort Lincoln New Town Corporation, Inc.] to enter into the same agreement the out of state developer had walked away from. Hagans, who had been closely involved in the negotiations, was intimately familiar with the terms of the agreement. In addition to a development timetable, it required Ft. Lincoln’s developer to commit to a twelve point plan for ensuring a substantial portion of the financial benefits, and long term profits, from the development went to District of Columbia job seekers, minority residents and future Fort Lincoln residents.

The unique provisions in Article VII of the agreement included requirements that: (1) the developer start a non-profit corporation, to provide community services, that would gradually be taken over by future Ft. Lincoln residents; (2) the developer donate $250,000, in installments, to the non-profit corporation and/or to a Homeowner’s Association to provide services for Ft. Lincoln residents; (3) the developer incorporate a real estate company, and convey at least 25% of its ownership to the resident’s non-profit corporation; and (4) that the developer ensure that even when third parties sell, lease or manage property in Fort Lincoln, those third parties turn over 10-15 percent of their gross commissions or fees to the residents’ non-profit corporation.

Balanced against these requirements were other terms that ensured the agreement would be extremely lucrative for the developer. The agreement committed hundreds of millions of dollars in public improvements to the development from the District and federal government– including streets, a huge park, schools and community facilities. The developer was not required to pay for the 176 acres made available to it, in advance. Instead, to minimize its carrying costs, the developer was only required to pay for each planned section after the development plan for that section was approved. Finally, the developer was given the right to incorporate the only real estate company with the exclusive right to sell and manage most of the newly constructed property in Fort Lincoln.

Because of the millions of dollars of profits involved, the RLA re-opened bidding for development rights at Fort Lincoln in March of 1975. It announced that the principal criterion for selecting a new developer would be the extent to which bidders indicated their intent to accept the previously negotiated Land Disposition Agreement without substantial changes. Four bids were submitted. The RLA concluded that only Hagans’ company, Ft. Lincoln New Town Corporation, met all the bidding requirements. A subsequent lawsuit, and request for an injunction filed by one of the failed bidders, was unsuccessful. As a result, the RLA signed a Land Disposition Agreement with Ft. Lincoln New Town on June 13, 1975.

Greed Trumps Compliance With Law and Contract

However, when the developer began renting and selling apartments and homes in Fort Lincoln in September of 1976 it did not disclose to the new residents their profit-sharing and decision-sharing rights – despite a condominium law and a D.C. consumer law that specifically required those disclosures, and required the developer to provide the newcomers with an actual copy of the LDA. Thus, to this date the developer has been able to exercise plenary decision making authority over the development and has reaped millions of dollars in profits exclusively for itself.

An essential part of President Johnson’s unprecedented initiative was the selection of a developer for Fort Lincoln who would partner with future Fort Lincoln residents to use the profits from the early rental housing (primarily senior buildings) built in Fort Lincoln to ensure that residents would have the financial leverage to have a say in its development going forward. But the developer (and the D.C. government, unfortunately) concealed that information from early residents of Fort Lincoln. And so the theoretical partnership never developed.

The Construction Timetable

Under the Fort Lincoln Land Disposition Agreement the District and federal government were responsible for building infrastructure and a school. The first building constructed was a public housing apartment building at the corner of Bladensburg Road and Banneker Drive, with 126 one-bedroom apartments for senior citizens and handicapped persons. The second building constructed was an elementary school, that was completed in 1975. However, it sat empty until 1979.

The first condominium development that Fort Lincoln New Town built was Cannon Village, which opened in 1976. Four other condominiums and four apartment buildings followed, with the last opening in 1991. There was then a long interlude, stretching into the 21st century. Premium Distributors, a beer distributorship opened in 2001, followed by a six year interlude. The year 2007 kicked off more than a decade of townhouse construction, with townhome developments opening in 2007, 2012, 2017 and 2019. Two comparatively upscale apartment buildings joined them in 2009 and 2019.

To the extent practical, the FLCA has adopted and advanced the goals that led to Fort Lincoln’s founding, by endeavoring, through its committees, to ensure Fort Lincoln’s (now) economically, and to some extent racially, diverse community has “a full range of educational, recreational, shopping and other services for people of different incomes.”

The Fort Lincoln Construction Time Line

Renamed Thurgood Marshall Elementary School in 1996

Fort Lincoln Senior Village I-Gettysburg Apartments

Fort Lincoln Senior Village II-Vicksburg Apartments

Fort Lincoln Condo II-Summit Village

closed in July 2013

Marshalls

Lowe’s Home Improvement

Dick’s Sporting Goods

Pet Smart

T-Mobile

Five Below

Visionworks

Starbucks

Panda Express

Jersey Mike's

Starbucks

Tropical Cafe

Transit Employees Federal Credit Union (TEFCU)

Jersey Mike’s Subs

Panda Express

Chik-fil-A

United Parcel Service

Vitamin Shoppe

Verizon

Dakota Nail Spa

Mecho’s Dominican Kitchen

Quickway Japanese Hibachi

Chipotle Mexican Grill

Vision Works

The Good Feet Store

Five Guys (May 2022?)

Mezeh (May 2022?)

Hook & Reel (May 2022?)

Plans for Fort Lincoln’s future development are discussed in

the “DAILY LIVING” section of this website.